Sound the alarm

Black children are in danger. From trauma to poverty to educational inequality to racism, our children face very real threats to their mental health every day. I distinctly remember being taught during my psychiatric residency training that black people don’t typically die by suicide; but sadly, this just isn’t true. Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States and the 2nd leading cause of death for people ages 10 – 34 years of age. For black youth, suicide is on the rise. In 2015, Jeffrey Bridge et al. discovered that suicide rates among black children ages 5 to 11 years increased from 1993 to 1997 and 2008 to 2012 while decreasing among white children in the same age range. Then in 2018, Dr. Bridge and his group found that among children ages 5 – 12, the rate of suicide for black boys and girls is double that of white children. Similarly, Lindsey et al. saw that that black teens (boys and girls) had an increase in suicide attempts from 1991 to 2017; and, for black boys, there was a significant increase in injury by attempt. Equally disturbing is that we don’t know why such significant age-related racial differences exist.

Sobering thoughts

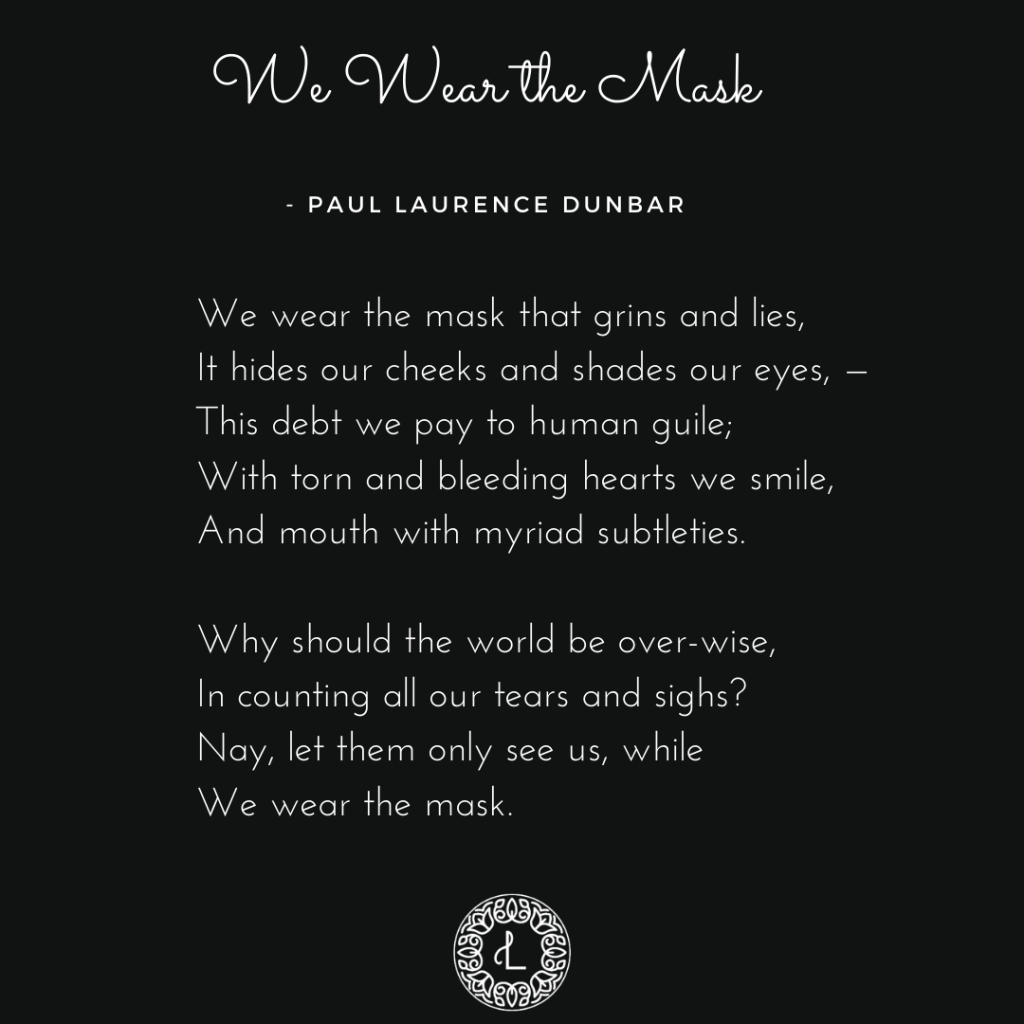

Many in the Black community prefer to avoid discussing mental health and mental illness. Stigma is real. No one wants to be labeled crazy. No one wants to risk losing their children because they seek mental health services. Those who are Christian don’t want others to think they lack sufficient faith or that they have turned their back on God. No one wants to have their fears invalidated or dismissed by culturally insensitive providers. No one wants to incur medical debt finding adequate care. No one wants to risk their life if they call the police during a mental health crisis.

Each of these issues are particularly salient for Black people. According to Merriam-Webster Dictionary, stigma is a mark of shame. Stigma also encompasses the attitudes and beliefs that lead people to reject, avoid, or even fear those whom they view as different or other. Stigma is the public’s perception, but it is also internalized. Under the weight of the perceived stain of mental illness, people feel misunderstood and less than, will refuse to seek treatment, and are fearful of what they stand to lose should they ask for help.

I have seen black men and women wary of diagnoses because such diagnoses become derogatory labels that hinder growth and progress in a society that has already vilified blackness and consistently dehumanizes black lives and mocks black pain.

Black women refuse medication for severe depression out of fear that child protective services will be called and their children removed from their home because an agent of the state deems her incapable of adequately caring for her children because of her depression or anxiety,

I know there are Black Christians who believe they must strengthen their faith and pray their depression away to be healed because someone in the church mistakenly told them that their depression is the enemy’s curse. Let me be clear, I know that God can heal and restore; but I also know that He has given the gift of supernatural healing to some His people. Jesus + therapy +/- meds all work together beautifully to cultivate wholeness and wellness. Mental health clinicians provide wise counsel.

We clearly need more mental health providers, psychiatrists, therapists, and psychologists of color AND those who have the training and cultural sensitivity to meet the unique needs of Black people. It’s not that your mental health provider must be Black, but he or she must be willing and able to acknowledge your lived experiences and create emotional holding space for your truth even if that truth flies in the face of their construct of reality all while ushering you towards psychological well-being.

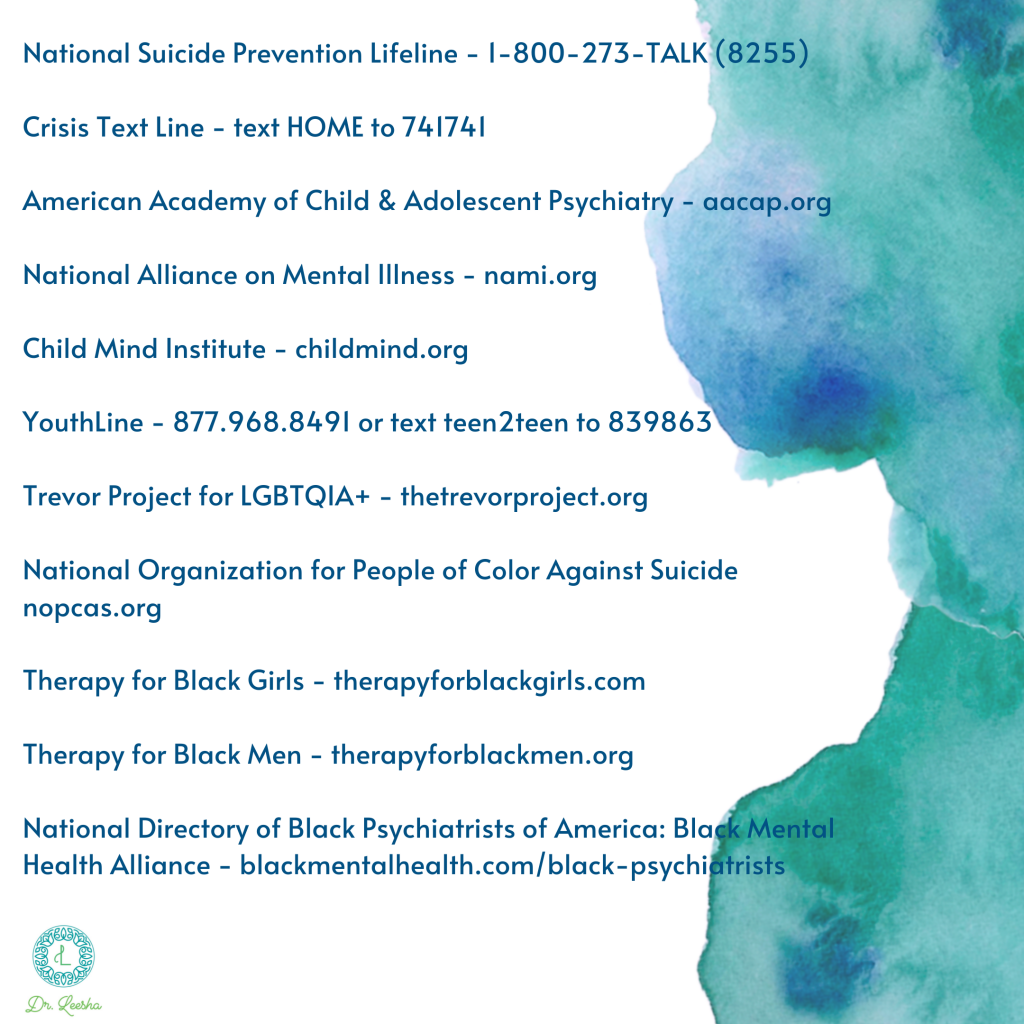

If you can’t access mental health services that are affordable, available, and reasonably close, then you won’t be able to get the help you need. Access to care is critical and an oft cited barrier to treatment. Black families need access but options for black families can be quite limited. A couple of suggestions include community mental health centers which are clinics that receive federal and state funds to provide services for children and adults, for those without insurance (at low out-of-pocket cost), and those who have Medicaid. Most are near public transportation as well. Typically, mental health clinics affiliated with academic medical centers provide counseling and psychiatric services on a sliding-scale. Additionally, there are private practices locally that accept various insurances or may see patients in a cash-based practice which means that provider does not accept any insurance.

What about Black children?

Statistics like the ones highlighted at the beginning of the post reflect what I see in the clinics where I work. Young black boys and girls are dealing with significant mental health challenges. Our babies are bullied at school and on social media, especially those with special needs and sexual minority youth. They are being neglected by parents and caregivers who must work long hours or multiple jobs to make ends meet. They are being physically or sexual abused or have witnessed unspeakable trauma. I treat children who have seen family members gunned down or themselves shot. I treat children who have been sexually assaulted by neighbors and family members. Our children struggle with food insecurity, incarcerated parents, parental substance abuse, and unstable housing. Sometimes, it’s poor self-esteem and fractured identity because black skin, natural coils and curls, and Afrocentric facial features aren’t celebrated or desirable unless it comes with touchdowns, home runs, and slam dunks. It’s the “n” world hurled at them and textbooks that only mention slavery, Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., and Rosa Parks. Or it’s the absence of other black students and black teachers at school, leaving them feeling unsupported or ignored.

So many times, we miss it. Parents, teachers, coaches, and church folk – we miss it! We see irritability and call it “an attitude.” We see academic struggles and call it laziness or lack of motivation and poor work ethic. We call him “soft” or “a punk” when he dares to cry or show pain which leads to toxic masculinity. We want her to suppress her pain, too. We gawk when she twerks and shame her for rapidly maturing body instead of recognizing hypersexuality as a possible symptom of sexual trauma. We miss it.

We, too, need to create safe space for our babies. They need us. They need us to see past the bravado, the sullenness and sulking, the acting out, and the anger. For behind all that may lie a deep well of unexpressed pain, and that pain is literally killing our children. In Alabama, we’ve had black children as young as 9 take their life within the last year. It’s happening around the country. It’s time that we stand up for our children.

Standing up for black children

We must discuss mental health and suicide because the very lives of black children depend on it. We must normalize vulnerability and transparency and make therapy something that black folks do, too. All adults, parents and caregivers, coaches, educators, community volunteers, must learn to recognize the signs and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and trauma. We must know the risk factors for suicide and act when we see warning signs. We must equip mental health practitioners with the training and skill to work with black families. We must create culturally informed guidelines and screening tools. We have to think outside the box to reach children of color. We must make it okay to not be okay, like for real. No more pleasantries and catchy sayings but truly allowing our precious black boys to shed tears and our beautiful black girls to question their value – all without judgment but refusing to allow them to get stuck there.

A Sudanese proverb wisely captures what we desire for our children:

We desire to bequest two things to our children — the first one is roots; the other one is wings.

– Author Unknown

We must root all of our children in love, self-awareness, individual and collective identity, a strong sense of community, an understanding of their rich legacy, and a thirst for complete wholeness. Then they will soar and fulfill their life’s work.